When I first opened Ranting Manor last year, I wrote on the home page that it would "record my experiences as a traveller and teacher of English". But I realised last week that, in actual fact, I've barely mentioned the teaching part at all.

There are a couple of reasons for this. First and foremost, I don't want to bore you! I mean, the occasional classroom anecdote is okay (I think), but I'm sure the vast majority of people reading this can live without a detailed breakdown of what it's like to teach English as a foreign language. And secondly, thinking back to when I was doing my training, I saw teaching partly as a vehicle. Which is to say that, while I thought it could potentially be a very suitable job for me, the #1 reason to be in a place like Moscow would not be to teach there but ... well, simply to be there.

That's why most of my rambling has centred on places I've visited and things I've seen while not explaining the present perfect, nit-picking phrasal verbs ("No, Tatiana, the opposite of 'put on your coat' isn't 'put off your coat' ... though it probably should be") or trying to help students distinguish between defining and non-defining relative clauses.

And now you're thinking "Oh ^deer^, he's about to launch into a whole bunch of wacky classroom tales." Well, sort of. What I want to do, now that my time in Moscow is just about over, is tell you what I think has been the heart of the experience for me.

It does, however, involve some teaching-related babble. Sorry 'bout that.

First, some context: the last few weeks have been mainly about saying "goodbye" to students I've met and taught here. Some of these farewells, it must be said, have been nothing short of sweet relief. I actually celebrated with a bottle of shampanskoye the day I was freed from the greasy clutches of my "Loser Class". This was a group of 10-13 year olds, most of whom had absolutely zero interest in studying English, but whose Novy Russkiy parents were pushing them to learn – presumably so that, in a few years' time, they can go to the English-speaking world and annoy native speakers in their own language. I could've strangled several members of this class, quite cheerfully and without the slightest damage to my conscience. The knowledge that I'll never have to see them again ... well, let's just say that knowledge can be a beautiful thing.

But then you had the other end of the spectrum: students whose company I've really enjoyed and who, in some cases, have proven rather difficult to leave.

Wednesday night's final lesson was a case in point. I had to farewell the last of my long-term adult classes, a very pleasant group of people who've been with me since I started in September. I really hadn't been looking forward to the day when I had to say goodbye to these guys, especially my favourite among them, an extraordinarily bright and conscientious young student called Masha Tretjakova.

Masha is one of those people who always manages to lift your mood, and her dedication to her studies is quite inspiring. But lessons must go on, so we opened our course books as per usual and explored prepositions of movement, until 9pm rolled around and it was time for goodbyes and best wishes. After the lesson, Masha decided to stay back and talk for a little longer. She gave me a gift, I gave her a gift, we chatted for a bit ... and then she started crying! I didn't really know what to do. But it was very gratifying to know I wasn't the only one who felt they'd gained a lot from teaching that class.

However, having said all that about the talented Ms. Tretjakova, I have to tell you that the real kicker for me happened three weeks ago. See, when I think about my personal Moscow highlights, there's one that stands out a mile; more than the amazing sights; more than the long-overdue break from Outer Anglo-world; more, in fact, than any aspect of the gradual Russian Revelation I've been caught up in for the last ten months.

Seeing Teens1 was the thing I most looked forward to every week as I plodded through other, less pleasant parts of my timetable, or as I coped with the various tribulations of life as a foreigner in Moscow. We did lock horns in a few early lessons, but with the inevitable teething problems sorted, teaching them became an absolute joy. More than once, they were my one and only reason to stay here when everything else was telling me to leave. And hey, look at that ... here I am, still sharing one of the world's great metropoli with ten-ish million people and an inestimable number of feral dogs. So obviously it was reason enough.

The irony here is that, at the start of my contract, I was warned at great length about the perils of teaching teenagers. "You give 'em the smallest chance or make the tiniest mistake, and they'll eat you alive", was one such warning I remember. Another was "Don't ever think that you can be their friend; they already have friends, and you're not one of them."

I've worked with some very capable teachers here and been given truckloads of solid professional advice. Fortunately, though, all of this "teens are incredibly scary" stuff turned out to be rubbish ... or at least a gross over-generalisation.

This was perhaps best demonstrated at New Year, which comes a week before Christmas in the Russian calendar. Whereas in Australia the big gift-exchange is done on Christmas Day, Russian people do it at New Year. I got a smattering of presents from students in various classes, but when it came time to see Teens1, fully half of them had gone out and bought me stuff. It was almost embarrassing (especially as I hadn't realised, and therefore had nothing to give in return), but also very cool. I got a couple of cards as well, including one from Sasha (more about her in a sec) which had a long passage of Russian text on the inside. Sasha had translated the text as follows: "That means, best regards from your crazy Russian friends and Happy New Year!"

I've never been a big one for greeting cards to be honest, but that card was an exception. I was tempted to photocopy it and stick it on the wall in our central school, near the senior teacher who had made a lot of the "teens will never be your friends" comments. But he disappeared to Siberia before I had the chance*.

I've actually got a little collection of cards from Teens1 now. My favourite came from Dasha, who was clearly the 'heart of the group' – the one who most often reminded me that learning is never a cold, impersonal experience if you enter into it whole-heartedly. Though she never meant to, Dasha could make me feel guilty for days afterwards whenever I delivered a mediocre lesson to Teens1 (and early on, there were quite a few of those!). But she could just as easily (and often did) send me off on a high when things went right in the classroom. Dasha continually surprised me by doing things like, for example, asking when my birthday was just a few weeks after we'd met, and then actually remembering five months later and making a gift for me.

That was textbook Dasha; it's difficult to imagine meeting a kinder, more thoughtful person.

That was textbook Dasha; it's difficult to imagine meeting a kinder, more thoughtful person.

Anyway, her card contained quite a lot of text, as is the way of things here. It read, in part: "This greeting card is for parents, but I chose it because I think that the teachers are the second parents. Thank you for everything, and I wish you good luck and the realisation of your dreams". Then later, translating the Russian greeting: "The best of all the presents ... here it is written that it is a parent's love. Teacher's love too, I think."

Of course, not everyone in the class was quite as expressive as this. Dasha was the youngest and, it seems, hadn't yet acquired the veneer of cool detachment that teens generally like to project into the world. So she tended to be a bit more forthright in her comments and reactions (though thankfully not to quite the same degree as some of my tiny studentini, who would do things like run up and hug me when I gave them their test results!).

So anyway, as I mentioned earlier, the joy of teaching this group is all in the past now. On May 31st we had our final scheduled 135-minute slot together. I'd been anticipating this for a while, of course, so I'd prepared a real "throw the course book out the window and let's have some fun" type of lesson, to try and make sure we ended on a high. I think it went quite well. But still, inevitably there came the "goodbye" moment.

As 7pm (the end of their lesson) approached, gifts and words were exchanged, and I told my beloved teens a few things I thought they deserved to hear – like, for example, that they're "a tiny bit famous", which they are among the Moscow teaching fraternity. ("Oh, so you're teaching in Butovo? You must have that teen class. I hear they're an exceptional group.") They seemed a little blown away by that; there were some slightly awed looks exchanged around the room, which were rather wonderful to watch.

I wish we could've hung out for a while and talked, but I had to kick the students out right on seven because I had another class starting almost straight away. So when the time came I just said "Thank you so much everyone, and goodbye". The reaction was kind of amazing; I was clearly asking them to leave, and they knew it, but they just ... well, no-one moved, basically. We all just sat there frozen, going "Hmmm, what now?" It came eerily close to being that "Captain, My Captain" moment – the one you're trained to think will never happen in real life.

I've never had a job this good before.

Eventually the students filed out, and I asked Sasha and Dasha to hang back for a minute. We chatted for a little while, and I managed to let myself stop thinking and just enjoy their company ... and then suddenly they were gone, and I was in the midst of my next lesson. Trying really hard to focus attention on my adult beginners, and their reading about Henry from Cambridge who works in a post office and goes to the cinema on weekends.

And that was that. Or at least I thought so.

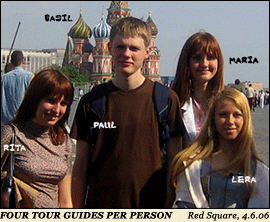

Two days later I mooched on down to Butovo School to meet my new short-term class of six-year-old psychopaths, feeling a little sorry for myself because that afternoon I would normally have had a lesson with Teens1. But when I got to the teacher's room Maria from Teens1 was there, waiting to speak to me. She told me that her and some of the other students had decided to organise a day out for us, and asked if I'd be available on Sunday.

Guess what my answer was. (Clue: if you're guessing "no", you haven't been paying very close attention.)

So off we trekked that Sunday into the centre of Moscow. The teens led me through Alexandrovskiy Sad – the garden of Tsar Alexander – explaining the historical &/or literary significance of every single thing we saw amongst its fountains and outdoor porticos. (I threw a coin into one of the fountains there, which apparently means I'm destined to return to Moscow some day). Then it was on to Red Square – my fourth time there, and it still gives me goose-bumps – followed by the glitzy Okhotny Ryad shopping centre and the main drag of Tverskaya Ulitsa. I'd seen most of this stuff before, but not with the expert commentary. The students really brought it all to life, making me feel something for places which had previously seemed like nothing more than random clusters of architecture.

One place I hadn't seen, mind you, was the inside of the McDonalds on Tverskaya. The teens had apparently planned to take me to a traditional Russian restaurant that day, but their plan fell through because none of them actually knew how to get there from Red Square. Plus, it was the hottest day of the year so far – pushing 30 degrees – and therefore possibly not the best weather for traditional Russian fare. After conferring for a while, they decided instead to take me where they go at the end of a fun day strolling around the city. So having begun beneath the elegant deco chandeliers of Chertanovskaya metro station, we ended our outing beneath the Golden Arches. Bit of a change of scene for me, I must say; the last two McDonalds restaurants I recall visiting were in Tokyo and Stockholm respectively, and in both cases I was purely there for the clean toilets. But I didn't mind at all. I realised that I was getting a genuine cultural experience here – a day in the life of my students. And I'm glad we didn't end up in some 'proper' restaurant where the students felt less comfortable, just because they thought I might prefer it.

To be honest, that was probably my best day in Moscow.

In some ways, my daily Moscow routine seemed a whole lot pointier when I had Teens1 to look forward to each week ("pointy" being the opposite of "pointless" if you base your knowledge of English on Buffy the Vampire Slayer – and I can't think of a good reason not to). Luckily, though, life here tends to have a fair amount of forward momentum; you continually get dragged along by what's happening in the present moment. That's sometimes a good thing (e.g. last Saturday when I went out to find a gym and ended up stumbling upon a beautiful 'nature corridor' I hadn't seen before) and sometimes not so good (e.g. my ongoing struggle to keep clean after the council turned off our hot water on June 2nd. We had to wait 19 days for the water to come back on.) But either way, the pace of life here tends to make 'dwelling on the past' an unaffordable luxury.

In terms of how I plan to follow up my Russian teaching experience ... well, I'll let you know when I know. In the meantime, if anyone's got a spare AUD$300 lying around, wire it to me tomorrow and I'll buy you a bottle of Kalashnikov vodka in the shape of an AK-47. It's cut-glass, it's life-sized, and it's one of the funnier / more disturbing things I've seen on sale in Russia. And believe me, everything is on sale here. Defenders of pure capitalism really ought to come and see how it mutates when let loose in the wild ... and maybe take a drive on Moscow's motorways, where Novy Russkiy trophy wives careen around in their beamers, holding driver's licences that their husbands bought for them when they bought the car. That's right; in the New Russia, there's no need to sit those bothersome driving tests if you've got the requisite purchasing power; you simply buy your way onto the road. It's a beautiful thing, don't you think?

Makes me wonder why I suddenly feel so sad about leaving ...

(Footnote, May 2010: in case you're interested, I'm still in touch with Sasha and Dasha, and they're all grown up now! Sasha is living in Vermont, USA, and Dasha is planning to marry her Beau some time in the future. Can't wait for the wedding )))

(*For people reading this in Kazakhstan: the person I'm referring to here is Daryl Koetzer. For others: I spoke to this guy two years later on the phone. He interviewed me for my job in Kazakhstan. Unfortunately, by the time I turned up in Almaty, he'd once again slipped away. But people like this have a habit of turning up again and again in the former Soviet world. I'm still hoping that I'll bump into Daryl one of these days. During the job interview he lied outrageously about life in Almaty, and so I have a lot to confront him about. But mostly, I want to show him the photos of me and a few of my favourite humans ... the ones he told me would "eat me alive". Clearly, the man has issues.)